How five tech CEOs are orchestrating the largest private infrastructure buildout in history — and who gets left holding the bag when the music stops

A Capital Expenditure Arms Race Without Precedent

Five tech CEOs are orchestrating the largest private infrastructure buildout in American history, and ordinary ratepayers are footing part of the bill. The Big Five hyperscalers — Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Oracle — spent roughly $256 billion on capital expenditure in 2024 and have guided toward $380–$443 billion in 2025, with combined 2026 commitments now approaching $660 billion. Goldman Sachs projects cumulative hyperscaler capex of $1.15 trillion for 2025–2027 alone, more than double the prior three years. To put this in context, Big Tech capex as a share of U.S. GDP now rivals the combined scale of the interstate highway system, the Apollo program, and broadband deployment. Harvard economist Jason Furman calculates that data center investment contributed 92 percent of U.S. GDP growth in the first half of 2025 — strip it out, and annualized growth collapses to 0.1 percent. America's economic engine is, for the moment, running on GPUs.

Five Companies Are Reshaping the American Power Grid

The sheer electrical appetite of these facilities defies easy comprehension. U.S. data centers consumed 176 terawatt-hours in 2023 — roughly 4.4 percent of all national electricity — and the Department of Energy projects that figure will reach 325–580 TWh by 2028, potentially 12 percent of total consumption. A single one-gigawatt hyperscale campus draws the equivalent power of 800,000 American homes. Georgia Power now needs 10,000 megawatts of new capacity, a 50 percent expansion of its entire fleet, with 80 percent flowing to data centers. PJM Interconnection, the grid operator serving 65 million people across 13 states, forecasts data centers could require over 50 GW of peak capacity by 2030 — enough to power every household in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, and Maryland combined.

The strain is already visible. In Northern Virginia's "Data Center Alley," which hosts over a third of the world's data centers, a minor grid disturbance in 2024 caused 60 facilities to switch to backup generation, shedding 1,500 megawatts instantaneously — roughly Boston's entire power demand — and nearly triggering cascading failures. ERCOT in Texas projects total load growth from 87 GW to 145 GW by 2031, with data centers accounting for 46 percent of that increase. This bottleneck has catalyzed a nuclear renaissance: Microsoft signed a 20-year agreement with Constellation Energy to restart Three Mile Island, Amazon committed $20 billion to nuclear-powered infrastructure, and Google struck the first U.S. corporate deal for a fleet of small modular reactors. Georgia's Public Service Commission voted unanimously in December 2025 to approve five new natural gas plants at a construction cost of $16.3 billion.

Residential Ratepayers Absorb Costs They Never Chose

These capacity investments carry a price that extends well beyond corporate balance sheets, illustrating what economists call negative externalities — costs imposed on parties who did not consent to the transaction. PJM capacity auction prices have surged more than tenfold in three years, from $28.92 per megawatt-day in 2024–2025 to $333.44 at the FERC-approved cap in 2027–2028. The PJM Independent Market Monitor found data centers were responsible for $9.3 billion, or 63 percent, of the $14.7 billion capacity bill for 2025–2026. Average household electricity bills across the PJM region have already risen $20–$30 per month since June 2025. The Natural Resources Defense Council projects that without reform, residential bills could climb another $70 monthly.

The pattern of public choice theory — where concentrated interests capture regulatory benefits at diffuse public expense — is vivid in the tax abatement landscape. Good Jobs First found that at least ten states lose more than $100 million annually to data center subsidies. Virginia's forgone revenue reached $1.6 billion per year by early 2026; a state legislative audit concluded the exemption does not pay for itself. Texas revised its projected subsidy cost from $130 million to over $1 billion in just 23 months. Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker announced a two-year suspension of new data center tax incentives. These subsidies represent a textbook transfer from dispersed taxpayers to concentrated corporate beneficiaries — precisely the dynamic public choice economists like James Buchanan warned about.

The Winners Are Real, but Concentrated

The boom has undeniable beneficiaries. NVIDIA posted $115 billion in data center revenue for fiscal 2025, up 142 percent year-over-year, with margins exceeding 75 percent. Vistra Corp's stock surged 258 percent in 2024. The U.S. data center construction market hit $48 billion in 2024, growing 90 percent in a single year. Rural communities from Abilene, Texas, to Saline Township, Michigan, are gaining construction employment and tax revenue. Yet permanent operational employment at completed facilities remains thin — a dynamic that concentrates gains among chipmakers, utilities, and construction firms while dispersing costs across millions of ratepayers. The American Farm Bureau Federation adopted new policy in 2025 warning that data center energy demand threatens agricultural power costs; gas turbine manufacturers report five-year backlogs that constrain power expansion for all customers.

The Circular Economy: When AI Companies Become Each Other's Best Customers

Beneath the headline capex figures lies a structural phenomenon that should give any Schumpeterian pause: the AI boom is increasingly financing itself. NVIDIA invests up to $100 billion in OpenAI; OpenAI uses that capital to purchase NVIDIA chips. OpenAI signs a $300 billion cloud deal with Oracle; Oracle rushes to build data centers packed with NVIDIA GPUs. AMD grants OpenAI warrants on 160 million shares of its stock; OpenAI commits to deploying 6 GW of AMD hardware. Microsoft invests $13 billion in OpenAI; OpenAI commits to purchasing $250 billion in Azure cloud services. The Washington Post described these arrangements as companies "propping up one another's finances, potentially beyond where logical and prudent spending would otherwise have taken them."

This is what analysts now call circular financing — a self-reinforcing loop in which suppliers, customers, and investors are the same entities. The mechanism is not new. During the late-1990s telecom boom, equipment makers like Lucent and Nortel extended vendor financing to buyers who could not otherwise afford their products, booking the resulting transactions as revenue. When demand forecasts fell short, the model collapsed spectacularly — heavily leveraged carriers slashed spending, filed for bankruptcy, and millions of miles of fiber optic cable sat dark for a decade.

The AI variant operates at vastly greater scale. OpenAI, despite generating only $13 billion in 2025 revenue, has committed to $1.4 trillion in infrastructure spending over eight years. The company reported $4.3 billion in sales but burned $2.5 billion in the first half of 2025 alone, and expects annual operating losses through 2028 — including a projected $74 billion loss in 2028. A Columbia Graduate School of Business analysis captured the systemic risk concisely: if Microsoft's AI monetization disappoints, it reduces Azure spending, which impacts NVIDIA's revenue, which affects CoreWeave's valuation, which circles back to OpenAI's funding capacity. The chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and every link depends on the same underlying assumption — that AI demand will justify the investment.

Venture capital has amplified the circularity. In 2025, 70 percent of all U.S. VC funding flowed to AI startups, up from 23 percent just two years earlier. Meanwhile, 80 percent of S&P 500 gains in 2025 were attributed to AI-related companies. The five largest firms now represent 30 percent of the S&P 500, the greatest concentration in half a century. For the 401(k) holders and pension funds riding this concentration, the diversification they expect from passive index investing has quietly evaporated.

When the Music Stops: Who Gets Left With the Bill

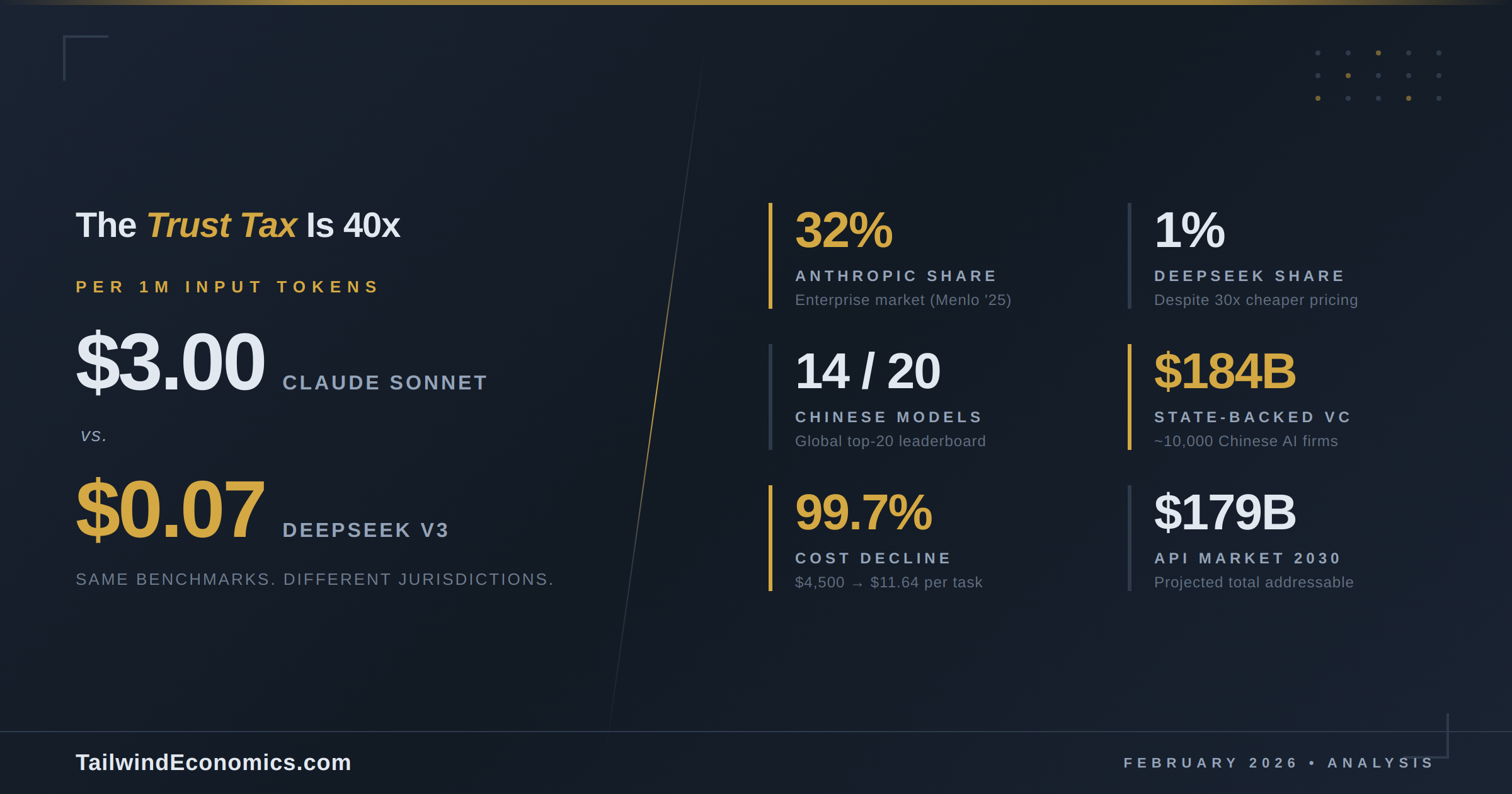

Joseph Schumpeter argued that capitalism advances through "creative destruction" — waves of innovation that render old structures obsolete while building new ones. The AI infrastructure buildout fits this framework, but with a crucial caveat: the destruction is already materializing in higher bills and strained grids, while the creation remains largely speculative. Total U.S. AI capital expenditures are projected to exceed $500 billion annually in 2026 and 2027 — roughly the GDP of Singapore. American consumers spend approximately $12 billion per year on AI services — roughly the GDP of Somalia. If you can grasp the economic distance between Singapore and Somalia, you understand the chasm between vision and reality.

A February 2026 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that 90 percent of firms reported no measurable impact from AI on workplace productivity. An MIT study found 95 percent of organizations investing in generative AI report zero return. Sam Altman himself acknowledged in August 2025 that investors are overexcited and that people will overinvest and lose money. Even Ray Dalio called current AI investment levels "very similar" to the dot-com bubble.

The concentration of decision-making is historically unusual. Satya Nadella, Sundar Pichai, Mark Zuckerberg, Andy Jassy, and Jensen Huang collectively control spending commitments that exceed the GDP of most nations. Morgan Stanley estimates Big Tech will need $1.5 trillion in new debt over the coming years, with $1.5 trillion of global data center spending between 2025–2028 covered by private credit — the opaque shadow banking system that regulators struggle to monitor.

There are early cracks. Data center project cancellations quadrupled in 2025 — 25 projects fully scrapped, representing 4.7 GW of demand. Microsoft quietly cancelled several hundred megawatts of leases. Peter Freed, Meta's former director of energy strategy, expects only about 10 percent of currently underway projects to reach completion. Community opposition has blocked or delayed $98 billion in projects, with 142 grassroots groups mobilizing across 24 states. Oracle's stock plunged 30 percent in the third quarter of 2025 amid doubts about its ability to deliver on — and collect payment for — its OpenAI commitments.

If the correction comes, the fallout will not be evenly distributed. The World Economic Forum's January 2026 analysis outlined a cascade: financial markets correct first, driven by a repricing of overvalued AI stocks. Smaller banks exposed to AI lending face deposit flight — a repeat of the Silicon Valley Bank dynamic. The cost of capital rises for non-AI sectors that were already starved of investment. Natural gas plants approved in Georgia and nuclear reactors restarted in Pennsylvania become stranded assets whose 30-to-50-year cost obligations fall on ratepayers regardless of whether AI revenue ever justified them. Pension funds overweight in the Magnificent Seven absorb losses that flow through to retirees. Low-income communities — disproportionately hosting data centers and already bearing the brunt of rising utility costs — face the compounding blow of economic contraction and locked-in infrastructure obligations.

The venture capitalist Paul Kedrosky drew a sharper historical parallel: massive capital spending in one narrow slice of the economy during the 1990s diverted capital away from American manufacturing, raising the cost of capital for small producers at precisely the moment Chinese competition intensified. The AI boom may be performing the same function — a gravitational "death star" pulling investment away from every other sector of the economy.

Conclusion

The AI data center boom represents an extraordinary experiment in oligopolistic capital allocation — a handful of firms leveraging market dominance in cloud computing and advertising to place a multitrillion-dollar wager on artificial intelligence demand that has yet to materialize at scale. The economic frameworks map neatly: Schumpeterian creative destruction in the remaking of energy infrastructure, negative externalities borne by ratepayers who never consented to the risk, regulatory capture in the form of billions in tax abatements that audits show fail to pay for themselves, and circular financing that inflates demand signals within a closed loop of interdependent firms.

What makes this moment distinct from prior technology bubbles is not the speculative excess — that is familiar — but the physical permanence of the bet and the asymmetry of who bears the risk. Five executives are making sovereign-scale spending decisions. Their shareholders may absorb mark-to-market losses. But the natural gas plants, the grid expansions, the forgone tax revenue, and the utility rate increases will persist for decades — paid for by ratepayers, taxpayers, and pension holders who never had a seat at the table. The fiber optic cables laid in the 1990s eventually found users. Whether the same will be true for a trillion dollars in AI infrastructure remains the most consequential open question in the American economy.